PostgreSQL: About Internals & Tuning

I attended Karen Jex’s talk on databases at DjangoCon in Edinburgh 2023. That sparked my curiousity. I find databases fascinating—they don’t change as fast and as much as other software, such as frameworks, yet they’re used in nearly every system we rely on.

I decided to spend this rainy weekend in Prague exploring the internals of PostgreSQL and writing down some notes from my learnings.

How Is Data Stored?

As someone who regularly works with databases, I know data is stored in tables, but how exactly are these tables stored?

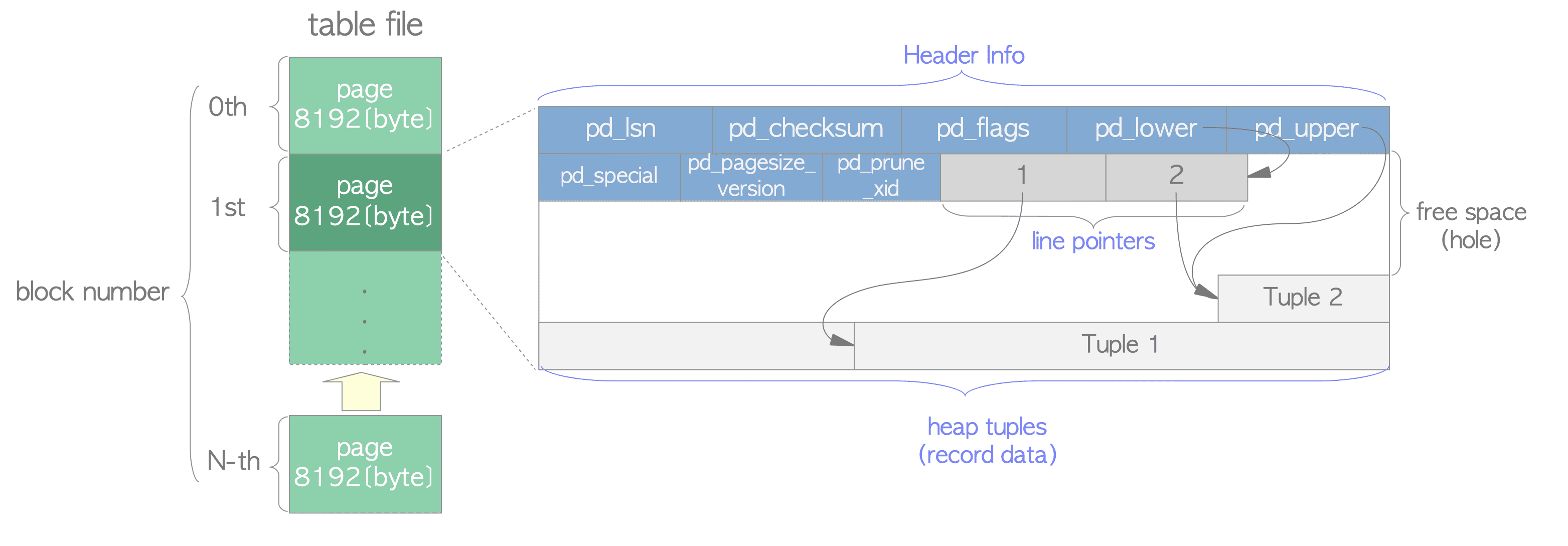

- Tables: Stored as heap files on disk.

- Heap Files: Consist of data pages (also called blocks), each typically 8 KB in size.

- Data Pages: The basic unit of storage in PostgreSQL, containing tuples (rows) and header information.

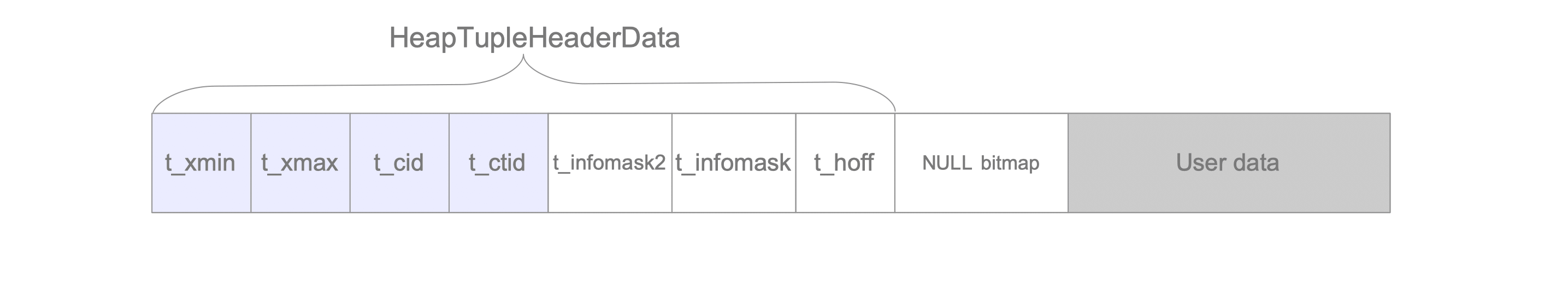

- Tuples: Each tuple consists of a header (metadata) and the actual data (column values). Tuples are not stored in any particular order.

Structure of a Data Page

A data page has the following components:

- Page Header: Contains metadata about the page.

- Line Pointer (Item Identifier) Array: An array of pointers to the tuples stored within the page.

- Tuple Data Area: The actual storage area where tuples (rows) are stored.

- Free Space: Unused space available for new tuples.

Line Pointer Array

Now that we’ve introduced data pages, we can explain the line pointer array:

- An array of pointers located immediately after the page header in each data page.

- Each entry in this array is called a “line pointer.”

- Each line pointer corresponds to a tuple (row) stored within the data range.

- It points to the offset within the page where a tuple starts.

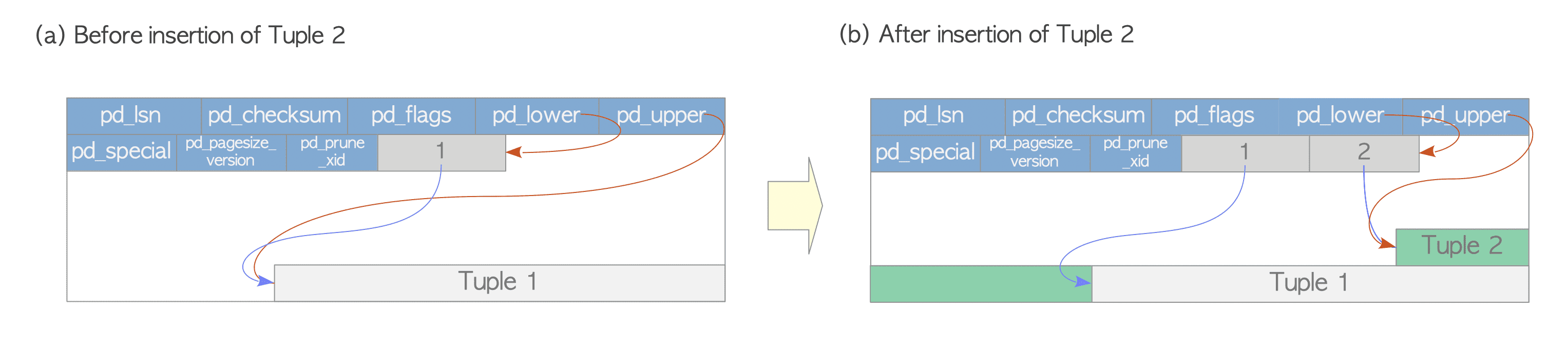

What Happens When a New Row is Inserted?

- PostgreSQL places the new row into a data page.

- The tuple for this row has a header (metadata) and the data itself (column values).

- The line pointer array contains a pointer to this tuple’s location within the page.

What Happens When a Row is Deleted?

- The row is marked as logically deleted (dead) by updating its metadata.

- Its visibility is changed so future transactions cannot see it.

- The line pointer still points to the row’s location, but it is marked as ‘dead.’

- The data remains on the page until a cleanup process (VACUUM) occurs.

What Happens When a Row is Updated?

- A new version of the tuple is created and may be placed in a different part of the page or even a different page.

- The line pointer array is updated to point to the new location of the tuple.

Internals

With an understanding of how data is stored, let’s check out other key concepts of PostgreSQL internals.

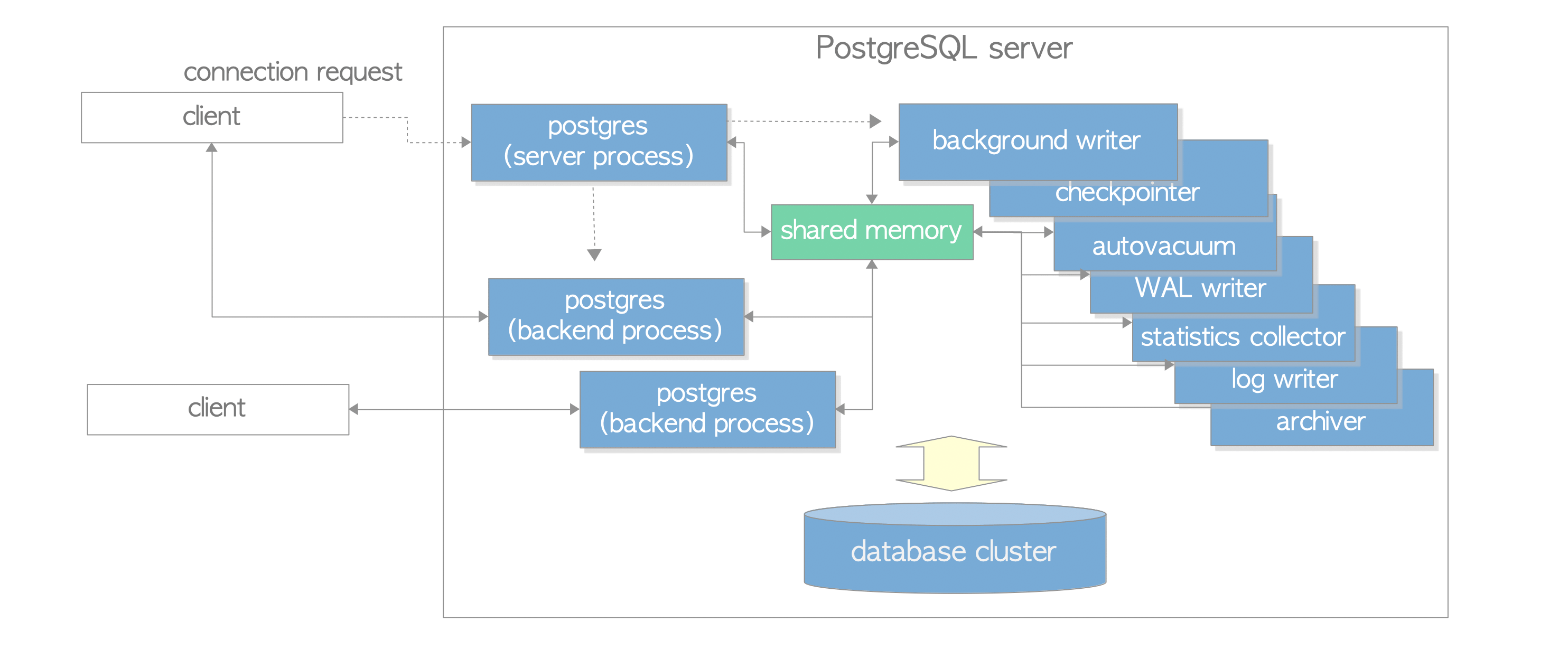

PostgreSQL follows a client-server architecture where each client connection is handled by a separate backend process. The database consists of various subsystems responsible for processing queries, managing memory, storing data, and many more.

Memory Architecture

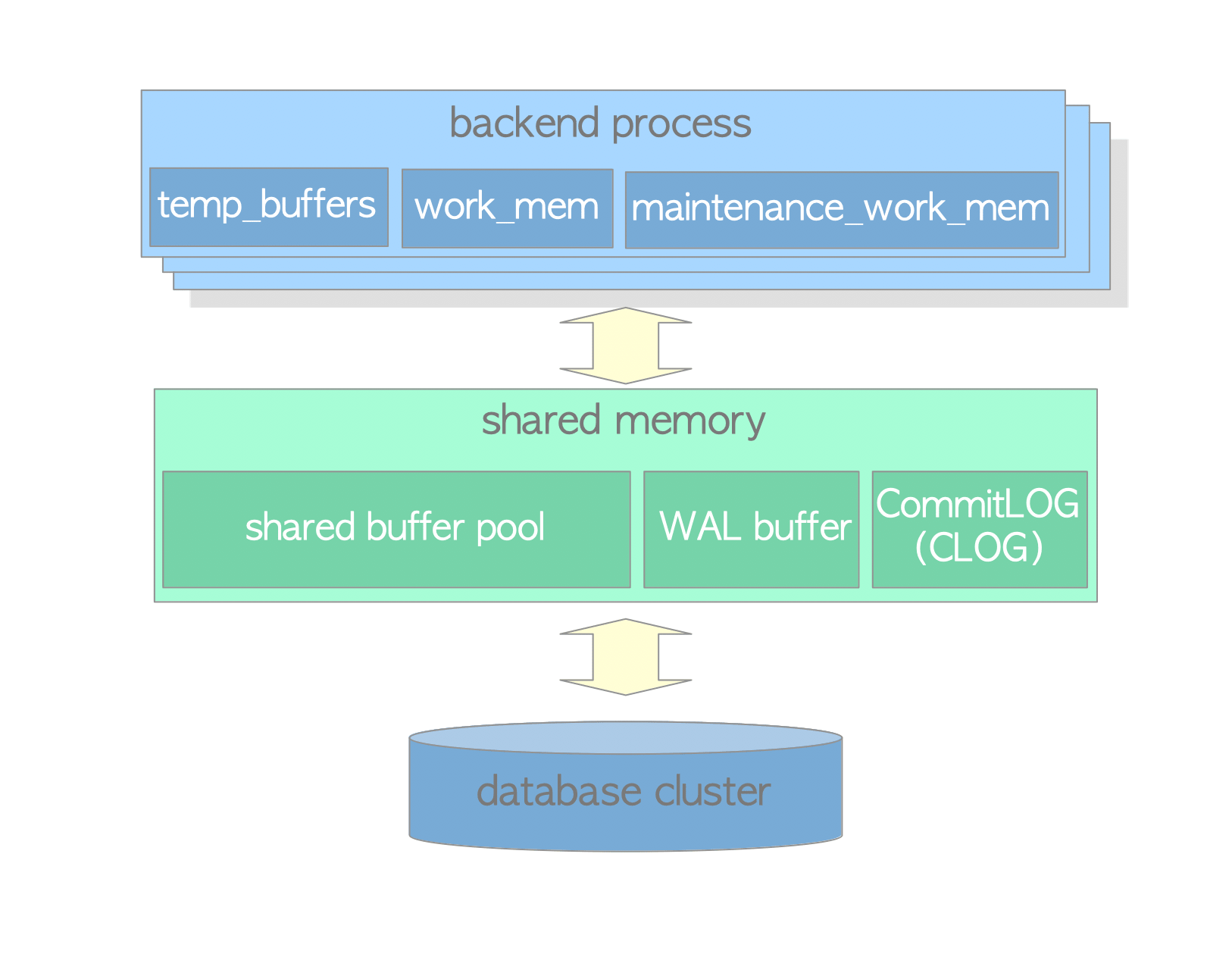

PostgreSQL’s memory architecture consists of:

- Local Memory: Allocated by each backend process for its own use.

- Shared Memory: Used by all processes.

Indexes

Indexes improve data retrieval speed by providing quick access paths to data. The most commonly used underlying structure is a B-Tree.

Index Lookup Process:

- Search Index: Find matching keys.

- Retrieve CTIDs: Get the physical locations.

- Access Data Pages: Use CTIDs to fetch tuples directly.

Without an index, PostgreSQL performs a sequential scan, checking each row in every page.

Difference Between an Index and a Line Pointer

- Index is an external structure to the table while a line pointer is internal to each data page.

- Index provides a mapping from column values to CTIDs, while line pointer points to the physical offset of tuples within the page

Query Path

Let’s see how a query is processed:

- Connection Established: A process is created per user.

- Query Sent: The client sends a plain text query to the backend.

- Parsing: The parser checks the query syntax and creates a query tree. It performs semantic analysis to understand the tables, functions, and operators referenced.

- Rewrite System: Applies rules to the query tree.

- Planning: The planner generates a query plan, choosing the optimal execution path.

- Execution: The executor steps through the plan tree and retrieves rows in the way represented by the plan.

VACUUM

Maintains database health by:

- Removing dead tuples.

- Freezing transaction IDs.

Two types of VACUUM:

- Concurrent VACUUM: Removes dead tuples while allowing other transactions to read the table.

- Full VACUUM: Removes dead tuples and defragments live tuples in the entire file, blocking access to the table during the process.

Write-Ahead Logging (WAL)

- Ensures no data is lost even in case of system failure.

- WAL records (XLOG records) are written to in-memory buffers and then immediately to a WAL segment file upon transaction commit or abort.

- PostgreSQL starts recovery from the REDO point, the location of the latest checkpoint.

How Does Replication Work?

The primary server continuously sends WAL data to standby servers, which then replay the received data.

How to Tune Postgres?

Now that you know the basics, you might be wondering if there’s anything you need to tune or if PostgreSQL just works as is. If you look at the documentation, you’ll find over 300 parameters, which can be pretty overwhelming. I came across Karen’s talk at DjangoCon, where she shared a list of the most important parameters to change from their default values. Here are my notes from her talk. If you’re interested in tuning PostgreSQL, I recommend watching the full talk!

Setting Parameters

- Cluster level:

postgresql.conforALTER SYSTEM SET parameter=value; - Database level:

ALTER DATABASE db1 SET parameter=value; - User/Role level:

ALTER ROLE bob SET parameter=value; - Session level:

SET parameter=value; - Transaction level:

SET LOCAL parameter=value;

Contexts

- Internal: Set during cluster creation, can’t be changed.

- Postmaster: Requires server restart.

- SIGHUP: Requires config file reload.

- Superuser-backend: Affects only new connections.

- Backend: Affects existing connections.

- Superuser/User: Can be set in the session.

Where to Find Information About Parameters?

- Documentation.

- Default

postgresql.conf. pg_settingsview. Example query:SELECT * FROM pg_settings WHERE name=’max_connections’;.

Connection and Session Parameters

- listen_addresses:

- Description: Addresses allowed to connect.

- Default:

localhost - Suggested:

*or0.0.0.0(all IPv4),::(all IPv6)

- max_connections:

- Description: Maximum concurrent connections.

- Default:

100 - Suggested: No more than

500. Use connection pooling if you have over hundreds of connections.

- idle_in_transaction_session_timeout:

- Description: Max idle time between queries in a transaction.

- Default:

0(disabled) - Suggested:

30 minutes

Memory Parameters

- shared_buffers:

- Description: Memory for caching data.

- Default:

128MB - Suggested:

25-40%of available memory.

- work_mem:

- Description: Max memory per operation before spilling to disk.

- Default:

4MB - Suggested:

10MB. Adjust per session for large operations.

- maintenance_work_mem:

- Description: Memory for maintenance tasks like VACUUM.

- Default:

64MB - Suggested:

~5%of total RAM.

Logging Parameters

- log_min_duration_statement:

- Description: Logs statements exceeding a duration.

- Default:

-1(disabled) - Suggested:

1sor as per system needs.

- log_line_prefix:

- Description: Information prefixed to each log line.

- Default:

%m [%p](timestamp and process ID) - Suggested:

%t:%r:%u@%d:[%p]:(timestamp, host, user, database, process ID).

WAL Parameters

- wal_buffers:

- Description: Memory for WAL before syncing to disk.

- Default:

-1(auto-calculated) - Suggested:

32MBfor many concurrent connections.

- checkpoint_timeout:

- Description: Max time between automatic WAL checkpoints.

- Default:

5 minutes - Suggested:

10-30 minutesto balance crash recovery and IO intensity.

- max_wal_size:

- Description: Sets WAL size that triggers a checkpoint.

- Default:

1GB - Suggested:

½ to ⅔of disk space in the WAL directory.

Query Tuning

- effective_cache_size:

- Description: Approximate memory available for operations.

- Default:

4GB - Suggested:

50-70%of total memory.

- random_page_cost:

- Description: Cost estimate for fetching a disk page.

- Default:

4 - Suggested:

1.1for SSDs,2.0for fast spinning disks.

Parameters to Avoid Changing

- fsync:

- Can cause database corruption if disabled.

- synchronous_commit:

- Risk of data loss.

- autovacuum:

- Essential for cleaning up dead tuples. Monitor with

log_autovacuum_min_duration=0.

- Essential for cleaning up dead tuples. Monitor with

What More to Pay Attention to?

I recently attended another one of Karen’s talks at PyCon UK called “How to Make Your Database Happy.” In addition to the parameters from above, she mentioned the importance of backups and high availability. Here are my notes from the talk.

Backups

If your data is important and you want to be able to recover it, you need:

- Somewhere to store it: A backup repository (preferably on a different server).

- Backup tool: Use tools like

pgBackRestorBarman. - Scheduling: Ensure regular backups.

- Online backups: Implement WAL archiving to save WAL files in a separate location.

- Enable archive mode and set up an archive command.

- Use

pgBackRestto take regular backups. - Backup = Copy of data + WAL.

High Availability

- Streaming Replication: Use PostgreSQL streaming replication to push data from the primary to replicas.

- Failover Management: Use tools like

Patronito monitor your cluster. If the primary fails, a standby can take over as the new primary.

Sources

- How to make you database happy?, Karen Jex: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=G7glaoEa9WQ

- Tuning PostgreSQL to work even better, Karen Jex: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7CnqVoMxoeo

- The internals of PostgreSQL, Hironobu Suzuki: https://www.interdb.jp/pg/index.html

- PostgreSQL documentation: https://www.postgresql.org/docs/current/index.html